Langley Township Council did not repeal its Community Amenity Contribution (CAC) policy because it was looking to help development in the municipality. They had to because the Supreme Court of British Columbia ruled that the policy was unlawful. At the July 21 council meeting, councillors gave final reading to an interim policy meant to patch over the legal crater left behind after the Township lost a landmark court case. The new stopgap allows developers to make voluntary contributions but attempts to eliminate any obligation, which, according to the court, was the problem all along.

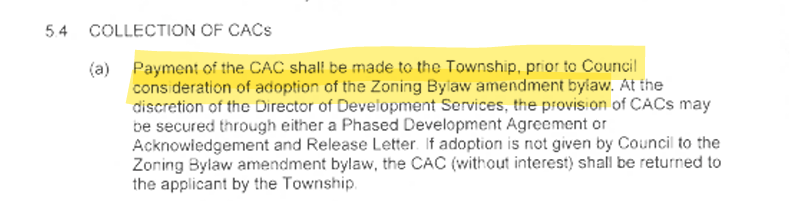

The ruling came in late June, when Justice Simon Coval found that Langley’s CAC regime went beyond what the law allows. The court said the Township had effectively turned developer contributions into a mandatory condition for rezoning. A move the judge called “not authorized under the Local Government Act.” Langley’s approach, the court found, crossed the line from policy into coercion. While most municipalities in B.C. have collected CACs, Langley took the model further, setting fixed contribution rates per unit and conditioning rezoning approvals on significant payments from developers. The court said that was not just heavy-handed. It was illegal.

The tipping point came when a major developer, behind a proposed film studio complex in Willoughby, refused to accept a multi-million dollar CAC payment and took the Township to court. The project never made it to camera, but the legal appeal did. The court sided with the developer, leaving the Township scrambling. Mayor Woodward dismissed the court loss as a “nothingburger,” pointing to the upcoming shift to provincially sanctioned Amenity Cost Charges (ACCs). But not everyone on council was as cavalier.

“Well, do we not have a number?” Councillor Kim Richter asked staff during the July 21 meeting how much the Township had actually collected under the now-invalid CAC program. Staff did not have an answer. She also questioned why the new ACC bylaw would apply to manufactured homes. Which she argued are a form of affordable housing. “Manufactured homes are actually affordable housing,” she said. “So why are they being charged?”

Councillor Barb Martens pushed for a minor amendment to the bylaw. One that would have explicitly required stakeholder consultation as well as a public information session. “I want to ensure we are in compliance with provincial legislation,” she said. Unsurprisingly, the mayor’s Contract with Langley bloc voted it down. Langley’s ACC bylaw is expected to be adopted by the end of the year. Unlike CACs, the new system is based on fixed formulas, transparent bylaws, and legislated authority. In short, it has what Langley’s old system lacked: legality.

Other municipalities, notably Vancouver, have also faced criticism over CACs, mostly for lack of transparency or consistency. But Langley stands alone in having its policy tossed by the courts. The interim policy now in place allows for case-by-case amenity contributions, provided developers sign waivers confirming the money is voluntary. It really is a duct tape solution, but one that staff and council hope will keep projects moving until the ACC framework is finalized.

Mayor Woodward has often pitched CACs as the financial backbone of his infrastructure ambitions. Big projects, no tax hikes. But that only works when the funding tool is clear, transparent, and legal. Now, with the court decision in effect, the council has no choice but to pivot. Woodward insists the switch to ACCs is seamless. But when a Supreme Court judge rules your signature policy unlawful, that is not exactly a seamless transition. That is a significant reset that the elected representative did not choose.

Leave a comment